Upper-level Setbacks Delenda Est – YIMBY Melbourne

The case against upper-level setbacks

Upper-level setbacks:

- increase embodied carbon,

- increase operational carbon emissions,

- increase construction costs, and

- reduce housing supply.

We explore each of these issues in some detail below.

1. Upper-level setbacks increase a building’s embodied carbon

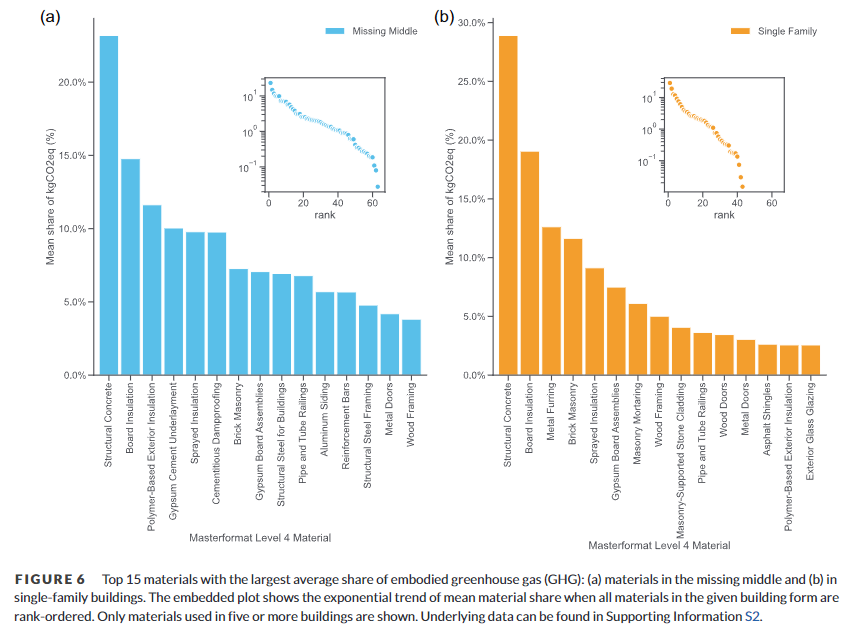

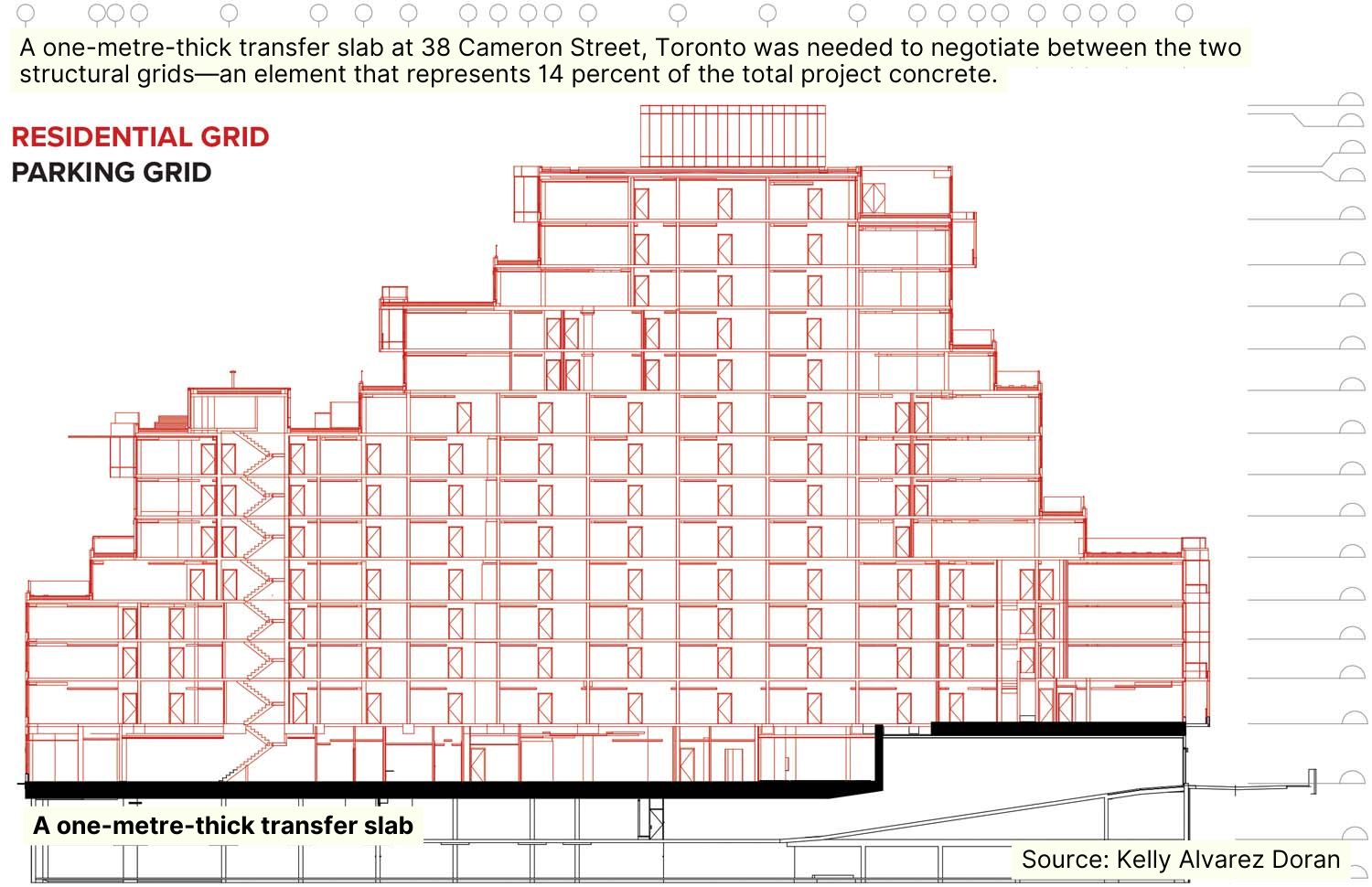

Researchers from the University of Toronto found that almost three quarters of the embodied carbon in a given build came from reinforced concrete, slabs, and drop panels.

“Design choices can yield large reductions in emissions,” write Rankin et al. in the Journal of Industrial Ecology.

In order to reduce embodied carbon, the researchers recommended the removal of setbacks.

Concrete slab volume, they write, “is a major driver of concrete emissions and could be reduced by building without [setbacks], which increase concrete load through large transfer slabs while reducing usable space.”

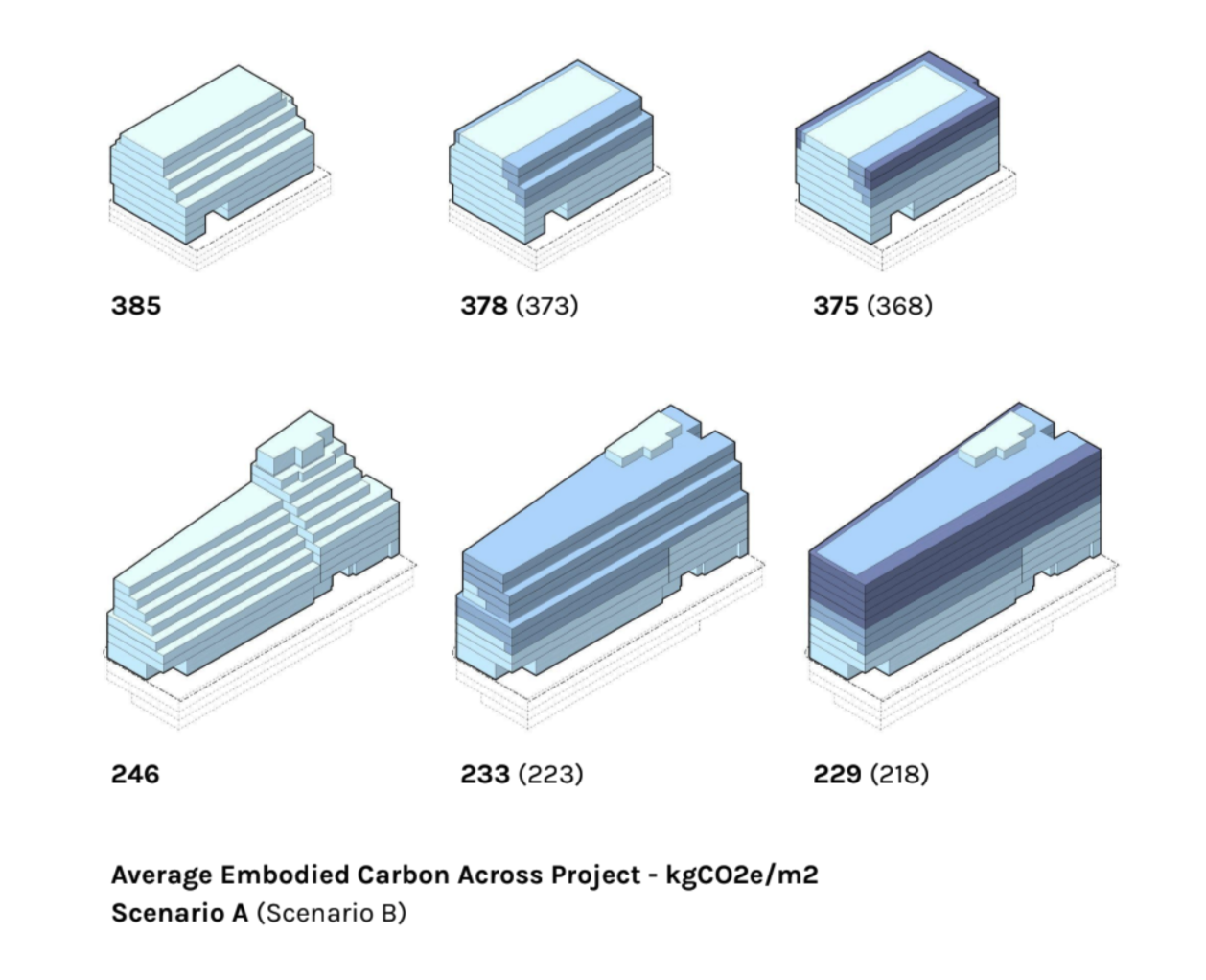

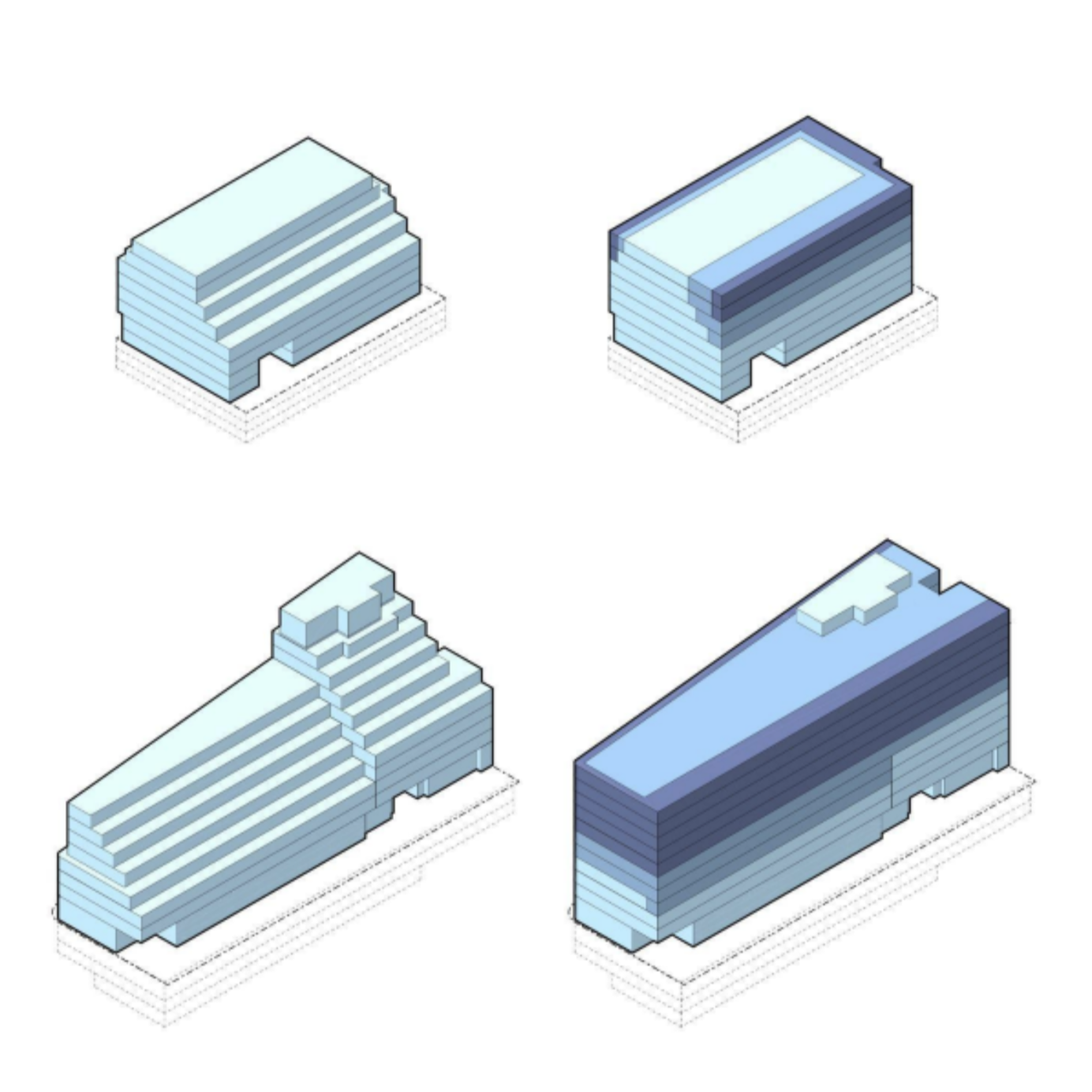

Also in Toronto, Half Climate Design developed alternate designs for two medium-density projects affected by upper-level setback controls.

The analysis demonstrated that the removal of setbacks would save between 10 and 17 kg of carbon per square metre built—even without moving to the more sustainable materials this alternative design would enable.

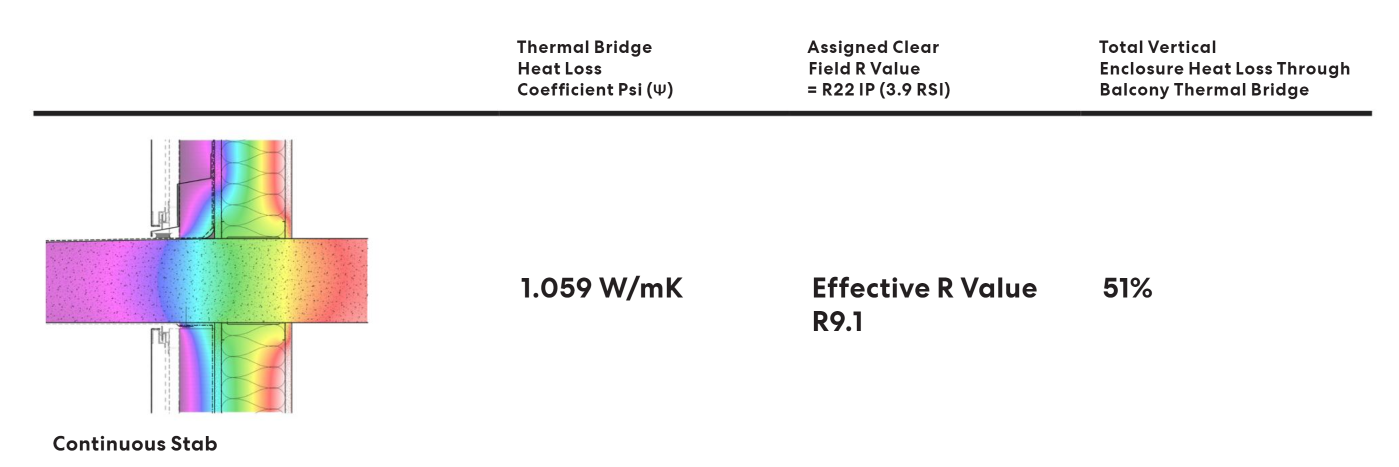

In addition to all of the above, setbacks also increase a building’s surface area and exposure to the elements.

This necessitates more thermal treatment and waterproofing, which is resource intensive and increases lifetime inefficiency of the building.

Which leads nicely to our next point.

2. Upper-level setbacks increase operational carbon emissions

Because setbacks require the extension of uncovered continuous floor slabs, buildings lose thermal efficiency due to heat transfer through exposed areas and structural concrete lacking shade from overhead balconies.

This increases heating and cooling costs for the building throughout its lifetime, and increases electricity bills for occupants.

As a fun bonus, due to the temperature of continuous floor slabs, setbacks also increase the risk of mould and condensation inside apartments. This is a terrible outcome for owners, and for the longevity of our city’s housing stock.

3. Upper-level setbacks increase construction costs

Buildings with a traditional “boxy” shape are simpler—and cheaper—to build and maintain, while more complex built forms are the exact opposite.

Upper-level setback controls raise the per-dwelling costs, which are then passed on in the sell prices of apartments within a given project.

This reduces project viability, and throws up yet another barrier to the increased housing supply our city needs.

4. Upper-level setbacks reduce housing supply

Moreover, setback requirements force developments to deliver less floor space—and therefore less housing.

How this happens is obvious when you look at a building with setbacks—all that empty space could have been more homes where people want to live.

The Half Climate Design alternate designs found that case study projects would have delivered 20% to 70% more housing if setbacks weren’t enforced.

| With setbacks | No setbacks | |

| 2803 Dundas Street West | 92 units | 113 units |

| 1100 Kingston Road | 146 units | 254 units |

Complying with upper-level setbacks forces architects to deliver highly-compromised and complex apartment layouts. This means fewer homes—and fewer family homes—within our apartment builds.

Removing upper-level setback requirements would enable housing projects to deliver more bedrooms, more family apartments, and more housing diversity to neighbourhoods across our city.

The (shaky) case for upper-level setbacks

Upper-level setbacks:

- Reduce wind tunnelling (but only on very tall buildings)

- Increase solar access (at the cost of shade and safety)

- Reduce ‘visual bulk’ (this is not a real thing)

Again, we explore each of these points briefly below.

1. Upper-level setbacks reduce wind tunnelling (but only on very tall buildings)

Many advocates for the current setback regime argue that they play a vital role in preventing urban canyoning or wind tunnelling.

The thing is—most evidence around wind tunnelling focuses on buildings above 20 storeys tall. There is little evidence that wind tunnelling is a major issue at low heights like those within Victorian planning controls.

Where wind tunnelling is a concern, it can be adequately resolved without upper-level setbacks through measures such as urban tree planting and the slight separation of buildings at the ground level.

Meanwhile, our city’s setback requirements sometimes start as low as 2 storeys, and apply to buildings well below 20 storeys total height, and ‘break up the form’ of our cities such that land use is inefficient, leading to more scarce housing, of a lower quality.

2. Upper-level setbacks increase solar access (at the cost of shade and safety)

Another notable argument in favour of upper-level setbacks is focused on overshadowing and sunlight. Indeed, current controls aim to maximise the amount of sunlight that hits our streets.

This aim, however, is falling under greater scrutiny in a warming world, where urban heat is considered a great threat to public health.

In a city like Melbourne, infamous for its cloudy weather, should overshadowing be our main concern, given the high cost of setbacks, and the fact that for a majority of the year the sunlight is diffuse anyway?

Indeed, recessing all our buildings comes at a great cost, including forgoing the benefits of shade for pedestrians, all the while disconnecting residents from their broader streetscape and neighbourhood, cutting off their connection from others and completely nullifying the safety benefits of passive surveillance.

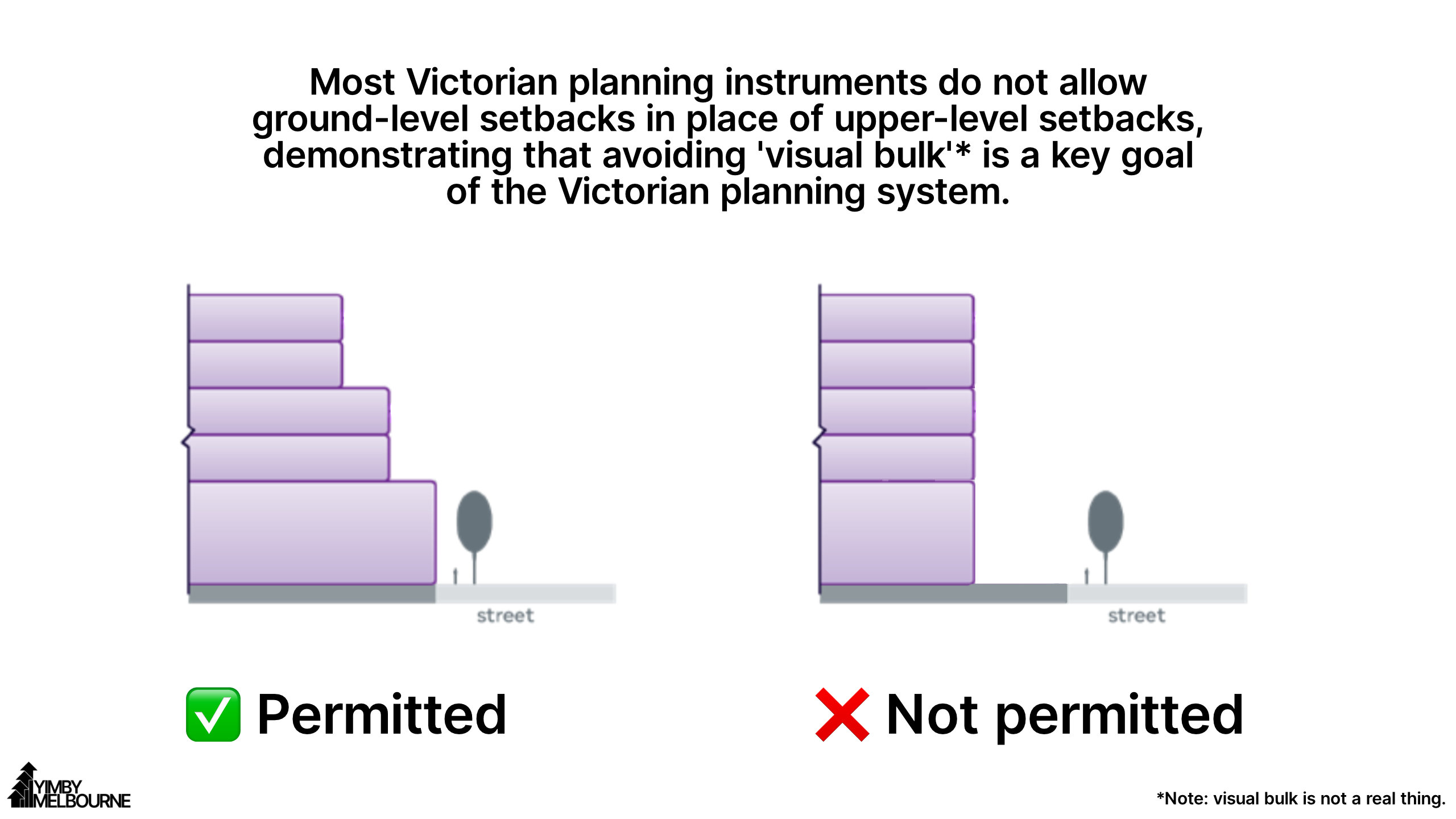

3. Upper-level setbacks reduce ‘visual bulk’ (this is not a real thing)

Let us be completely clear: visual bulk is not a real thing. It is a term entirely invented by anglospheric planning systems, and no material evidence exists that ‘visual bulk’ is actually a negative in urban environments.

And yet this invented term is the governing reason our system requires upper-level setbacks.

The two concerns above—wind tunnelling and solar access—could both be nullified in large part through ground-level setbacks.

However, the planning system does not consider ground-level setbacks to be a substitute for upper-level setbacks.

If you set your building back at the ground level, you cannot just build straight upward. You then have to also implement an upper-level setback.

Why? Because of “visual bulk” which, again, we have to stress, is not a real thing.